A Quick Overview of Yield Curve Inversions

What are Yield Curves and why do economists think they can be used to predict recessions?

The careful study of yield curves and their relationships can offer a practical glimpse of economic theory in action, and a view into the present and anticipated future states of an economy. Every now and then, when certain curves “invert,” numerous articles are written to alert the investing public that the inversion has occurred, to opine on what this means for the future of capital markets and the economy at large, as well as to argue the underlying causes of the inversion.

In a brief article on Seeking Alpha, Jason Capul writes,

The yield curve inversion that has marked fixed-income trading for the past several months deepened again on Monday. The spread between the U.S 10 Year Treasury yield (10Y) and the U.S. 2 Year Treasury yield (US2Y) have reached its widest point since 1982. … Historically, elongated periods of inversion have preceded economic downturns.

In Forbes, an article titled “Yield Curve Inversion Deepens, Increasing Likelihood Of 2023 Recession” by Simon Moore states,

The yield curve is now deeply inverted. Three months rates are well above ten year yields on U.S. government debt. The current inversion is deeper than before both the financial crisis and the 1990 recession, though not quite yet at the level before the dot com collapse of 2000.

Many voices are predicting a U.S. recession, from Jeff Bezos to many of the Fed’s own policy-makers in their economic projections. Still, the yield curve is among the more robust signals that a recession could be coming in 2023.

But: What is a yield curve? What is meant by “invert”? How, if at all, does this phenomenon relate to economic conceptual relationships as theorized by Austrian writers?

Setting the Stage: Bills and Notes and Bonds, oh my!

The US treasury offers financial instruments for market actors to lend money at a specified return across varying term-lengths. Here is the categorization of the instruments by term-length in brief:

Treasury Bills, T-bills: mature in one year or less.

Treasury Notes, T-notes: mature in periods varying between two years and ten years.

Treasury Bonds, T-bonds: have maturities of 20 or 30 years.

For simplification, this article will use the term “treasuries” to refer generally to the financial debt instruments issued at varying term-lengths.

Treasuries are debt instruments that are offered at a "price" to lenders, and are auctioned by the US Treasury. In purchasing one, market actors lend the face-value of the treasuries in return for fixed interest payments at known points in time until the instrument has matured, whereby the lender receives the face value initially foregone. These instruments are considered risk-free, as there is virtually no risk of default.

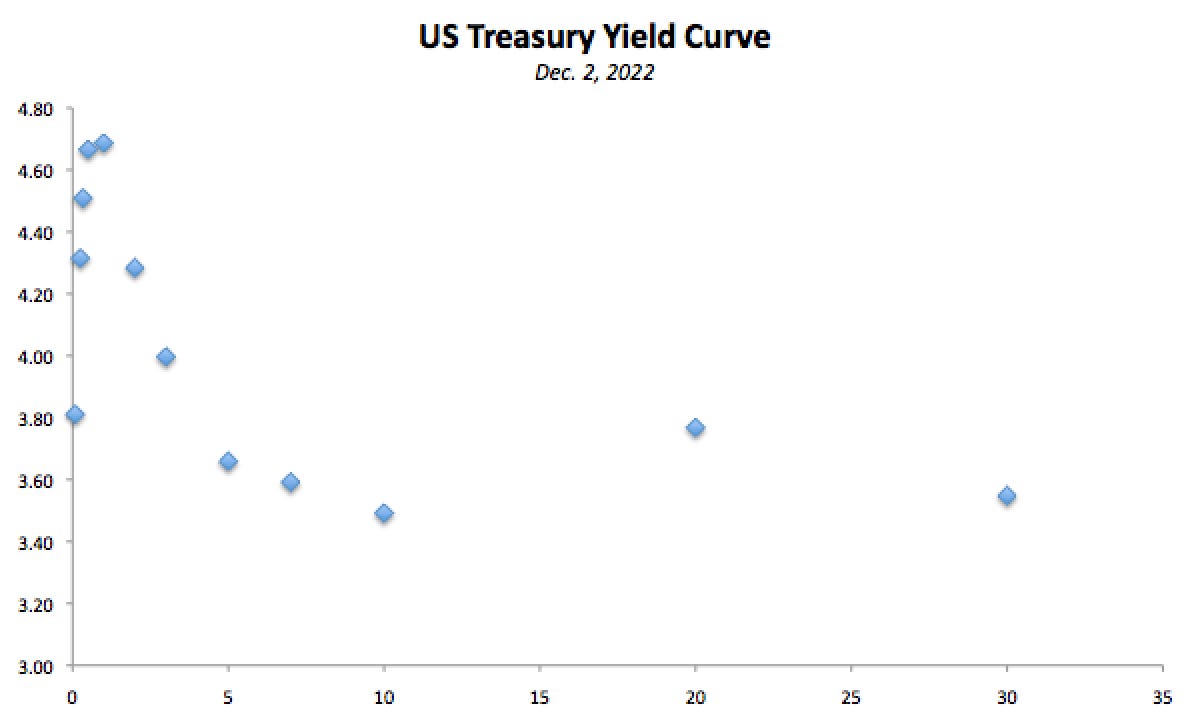

In assessing whether to acquire treasuries, investors will look at the yield. This is a comparison of the sum of interest payments until maturity to the face-value of the instrument. A 1-year $1,000 T-bill with two semi-annual interest payments of $10 will result in the payment of $20 in addition to the face-value of the T-bill upon maturity, one year after purchase. The yield is 2% in the case where the underlying face-value does not change. This sort of a relationship can be plotted for any financial instrument operating in this manner. In plotting these treasuries across a graph, with yields plotted on the y-axis, the typical shape of a “yield curve” looks like this:

Why is this shape considered typical? In lending money, the lender agrees to forego access to the amount lent for a specified term. Considerations on the part of the potential lender include the loss in value of the monetary unit over time, the risk of the borrower defaulting (effectively removed in the case of treasury markets), and arbitrage opportunities forgone with the amount over the term of the loan. For these general reasons, instruments with longer term-lengths to maturity can be expected to have higher yields compared to instruments with shorter term-lengths as a matter of the market process. However, there have been instances where treasuries with shorter term-lengths offered higher yields than longer term treasuries, and for sustained periods.

The Inverted-Yield Curve

The Inverted Yield Curve generally refers to the comparison of yields whereby a treasury of a shorter term-length offers a higher yield than a treasury with a longer term-length. Investors and market observers take notice when certain inversions occur, as they have historically been correlated with stock market downturns and recessions.

Investors generally place emphasis on the 10 - 2 year curve as a signal of upcoming recession. An article from April this year, when there was some worry about the curve inverting, cites commentary from BCA Research: “The 2-year/10-year Treasury slope has inverted in advance of 7 of the past 8 recessions and has not sent a false signal.” Economists Bob Murphy and Paul Cwik focus on the 10 year - 3 month curve, which has a “stronger” track record of preceding recessions in the sense of giving fewer false negatives and false positives. In Understanding Money Mechanics (UMM), Murphy shows a less recent version of the below graph and comments, “Notice in our chart that whenever [the 10-year and 3-month treasury inversion] happens—and only when that happens—the economy soon goes into a recession (indicated by the gray bars)” (Murphy, 122 - 123).

Writing in 2021, Murphy did not have access to the most recent inversion, which appeared for a day in the middle of October, and then again later that month and has stayed inverted since. Below is a graph focused on this period:

The day before Thanksgiving, the inversion in yield between the 10-year and 3-month treasuries reached -0.69, a difference that has not been seen since 2000 in the midst of the dot com bust - steeper than inversions between these two series in the prelude to the 2006-2007 recession, per FRED data. On December 2nd, the inversion between the 10-year treasury and the 3-month treasury reached -0.83, tying with December 14th, 2000 for the third largest inversion since 1982 where FRED tracking begins (largest inversion between these two instruments is February 16, 1982 at -0.96). There is a shorter-term instrument, the 1-month treasury - and the yield curve between this instrument and the 10-year inverted mid-November:

Economist Paul Cwik comments that the inversion of the 10 year and 3 month treasuries is a meaningful indicator of a recession occurring in the next four to six quarters on the basis of historical review of these series and subsequent recessions.

What are the economic factors at play when yield curves invert?

In the treasury markets, debt and credit is being exchanged in the form of risk-free treasury instruments. As Murphy comments in UMM, a graph reviewing 3 month treasuries against 10-year treasuries as two series on the same graph shows the yield on the 3-month treasury rising more quickly than the 10-year treasury as the source of these inversion episodes (page 124). Below is a graph inclusive of the most recent inversion between these two instruments where this pattern can be observed.

The current inversion is relatively unique in that, compared to previous episodes, both series rise considerably preceding the inversion whereas it’s more common for the 10-year to either remain fairly unchanged or even decline as the 3-month treasury yield rises. One possible reason for the longer-term instrument’s rising yield is concern with reductions in the future value of the dollar during the term of the loan.

Cwik describes the relationship starting from the basic supply and demand framework. “In order for the short-term rates to climb, there must either be a decrease in the supply of loanable funds, an increase in the demand for loanable funds, or a combination of both forces.”

Starting in the first quarter of 2022, the Federal Reserve has raised the target Federal Funds Rate at each of its FOMC meetings. As the below chart shows, the recent rate hikes have been the fastest in recent history. Ceteris paribus, as these hikes enter the loanable funds market, the cost associated with short-term funds available for interbank lending and borrowing increases, which tends to reduce the supply of loanable funds compared to circumstances without these hikes.

Finally, compare the shape of the below yield curve with the example of a typical curve in the first chart above. All instruments with shorter terms than 10-years are offering higher yields than the 10-year. Additionally, the only treasury with a lower yield than the 30-year bond is the 10-year.

CNBC RT Quote as of 12/2 for all treasuries

Other Articles Like This One

Europe Continues to Suffer From Massive Inflation

Learning Economics: Breaking Through Plateaus and Confusion

Discover New Opportunities

Click here for the Austrian Economics Discord Server.

Click here for the Austrian Economics Discord YouTube Channel.

Click here to get your very own “Swolerno” premium T-shirt for only 25 smackers! Available in 3 different colors.

The link to the discord doesn’t work