What Economists Get Wrong About Marginal Utility

Some economists argue that there are exceptions to the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility. They are wrong.

By J.W. Rich

In this week’s expedition to the island of misfit ideas, we will be examining the peculiar phenomenon of the Veblen Good. First formulated by Thorsten Veblen, it describes a good where the demand for the good increases as price increases. While at first this may sound like an impossibility, there are examples of this type of good that we can see in the real world. For example, part of the appeal of many designer fashion brands is precisely that they are so expensive. They are more than just clothing – they are a status symbol. The same is true for many other high-priced brands as well, where the high price is a large part of the appeal. As a result, the demand for these goods increases as the price increases.

For conventional economic analysis, this poses and obvious and uncomfortable problem. After all, the supposedly immutable Law of Demand clearly states that as price goes down, demand goes up. The mere existence of Veblen Goods seems to put this bedrock assumption of economics in dire jeopardy. Do we have to throw out two centuries of economic theory and start from the ground up? Not so fast. We can explain Veblen Goods, but to do so, we have to return to our basic principles – specifically – the definition of an economic good.

What is it that determines whether something qualifies as a good or not? This seemingly straightforward question is deceptively complex. It makes to say that a sandwich is a good, but what about 100,000 sandwiches? Such a large number of sandwiches would be unwanted, and thus, would not be a good. But why is one sandwich a good but not 100,000? The only way in which we can ground the definition of a good is not in any properties of the objects themselves, but in our perceptions of them. What determines a good is the suitability is has in satisfying ends that we seek after. We can easily conceive of having an end to eat one sandwich – if we are hungry, in need of nourishment, or simply want to eat something – but what need could someone have of 100,000 sandwiches? The former accomplishes and end, while the latter does not, which determines the difference in “goods-character” between the two.

How do we classify goods? We do so according to the ends that they fulfill. I consider three different sandwiches to all be the part of the same stock of goods so long as I can fulfill the same ends with all of them. They would all be considered part of the same stock of goods. However, if one of the sandwiches happens to be much less filling than the others, such that eating it would satiate only a small portion of hunger, it would not be considered a good equivalent with the other two sandwiches. Instead, it would be considered in as a good separate from the stock of the other two.

What does all of this have to do with Veblen Goods? Well, when we are considering the prospect of increasing supply along with increasing demand, we have to ask ourselves: are these the same good? The answer is that they clearly are not. The reason being that when a good is perceived as being higher value because of its price, it has a different suitability for achieving our ends than that same good at a lower price. As a result, they are not the same good, even though their physical characteristics are identical.

We can show the varying suitability of goods at different prices under subjective preferences with the following illustration. Let us suppose that an individuals has a scale of values that are arrayed like so:

1 - $100,000

2 – a car costing $90,000

3 - $90,000

4 – a car costing $60,000

5 - $60,000

6 – a car costing $35,000

7 – $35,000

8 – a car costing $15,000

9 - $15,000

The result of these subjective preferences is that as the price of the car increases, it occupies a higher place on the value scale. Looking only at the physical goods themselves, this gives the impression that there is an upward sloping demand here. However, as we stated above, in the case of Veblen goods, these are different goods that we working with. We can see this because of the differing valuations of the goods according to their price. If they were the same good, then there would be no reason for their separate placement on the value scale. The fact that we separate them indicates that the suitability they have towards achieving ends is not equal.

Many of the gravest economic fallacies are due to a small but foundational error. The supposed problem of Veblen Goods is exemplary of this fact. We do not have to throw out economic theory or even qualify our statements about demand because of the alleged troubles these goods propose. All that is necessary is for us to return to our definitions and solidify our understanding of our economic foundation. Is it only when this foundation is solidified that sound economic theory can result.

Read More by J.W. Rich:

thejwrich.medium.com

Discover New Opportunities

Click here for the Austrian Economics Discord Server.

Click here for the Austrian Economics Discord YouTube Channel.

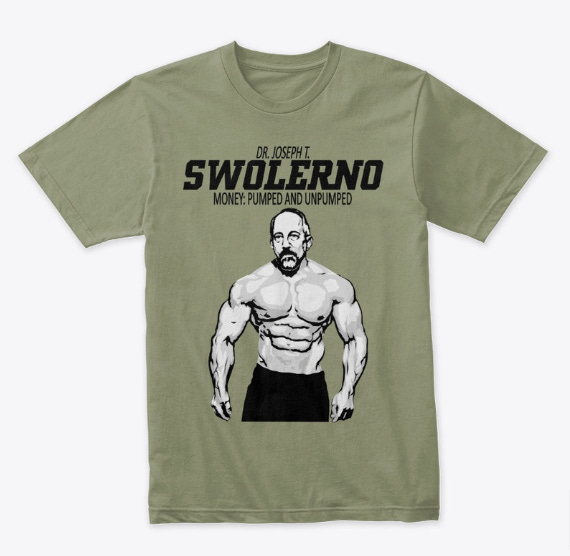

Click here to get your very own “Swolerno” premium T-shirt for only 25 smackers! Available in 3 different colors