Picking up the Pieces of Hyperinflation

Exploring the currency of one of history's most crippling episodes of hyperinflation.

By J.W. Rich

If you are looking for a new hobby, I would highly recommend starting a hyperinflation currency collection. This hobby is fantastic for two reasons: first, hyperinflation currencies are by their very definition next to worthless, so it doesn’t cost much to get in on the action. Secondly, they make for great antiques, but more specifically, antiques that tell a fascinating story. Allow me to illustrate with some notes from my own collection:

Pictured below is a one hundred Mark banknote from Germany, printed in 1908:

While looks are subjective of course, I think that these old styles of banknotes still look absolutely incredible. There’s lots of little details that make the note really stand out. For example, the ornate lettering in the “R” in Reichsbank (the central bank of Germany), as well as the “E”, “H”, and “M” in the following line. Even the “100” on the lower left has little flourishes hidden in the numbering, which you might miss at first glance. Behind it all is the imperial eagle of Germany, with the Kaiser’s crown at the very top.

That’s just the front, however. Pictured below is the back of the note:

Over a century later, this illustration is still captivating. While I haven’t ever been able to find a clear explanation for what the picture is supposed to mean, my guess is that it is supposed to represent a personification of the German people - a “Germania” of sorts - looking at the banknotes and having their collective image staring back at them. Regardless of the exact meaning, it gives the banknote a special cultural flair, reminding us of the time and people that created these notes in the first place.

This note was made before the First World War - six years before, to be exact. Before the war, the value of the German Mark had remained fairly stable. Because of the Bank Law of 1875, the German government was limited by the gold supply in how many notes it was given permission to print. As such, the Mark maintained a relatively stable value for decades. The war would change that forever. Whenever Germany entered the war, it quickly found itself faced with a potentially crippling problem: the government didn’t have the money necessary to maintain wartime expenditures. Britain and France were also facing financial problems as well, but they had access to international investment funds, which allowed them to fund a large portion of their war effort through debt. Germany did not enjoy this luxury. The result was that the German government would be forced to choose between three options (or choose varying degrees of all three): increase taxes, issue more bonds for the German people to buy, or print more money. The German people could only buy so many bonds, and it was seen as politically unpalatable to increase taxes. The result is that the lion’s share of Germany’s war effort would be fueled through inflation of the currency and continuous money printing.

While the war would cause unimaginable destruction on the front lines, the inflation of the German mark would cause havoc on the home front. Inflation ravaged the German people, as the prices of necessary goods like bread and eggs kept increasing year after year. When combined with the increased scarcity of these goods, the standard of living of ordinary Germans plummeted throughout the war years. Eventually, Germany would be forced to end the war, signing the infamous Treaty of Versailles. Even so, the value of the mark would only continue decreasing. At the start of the war, the mark was worth 1/20 of a British Pound. By the end of the war, it was trading at only 1/43 to the pound. By the time the Versailles Treaty was officially signed in 1919, it was down even further to 1/60. Over the course of 1920, 1921, and 1922, the inflation would only accelerate as the political situation destabilized and the government continued printing increasingly quantities of money. By 1923, the reality on the ground was undeniable: Germany was in a state of hyperinflation.

We can see the deterioration of the Mark’s value in the banknotes from the time. For example, pictured below is a fifty thousand Mark note from 1923:

While ostensibly worth more than the one hundred Mark note we saw above, this note would have been worth significantly less when it was printed in August of 1923. By that point, the Mark was trading at 1/69,000 of a British Pound. Whereas the one hundred Mark note above would have traded for five Pounds when it was printed, this 50,000 note was worth not even a single Pound.

More interesting than the value of the note are the details of the note itself. Compared to the one hundred Mark note, this note is very simple and plain. It doesn’t utilize highly stylized fonts, detailed illustrations, or even the more intricate watermarks all present on the one hundred Mark note. Even more fascinating is that the back of the note is completely blank:

In fact, each note from this point forward will be exclusively one-sided. Their backs have not been printed on at all. While this was partially to save on ink costs, the real reason was that it made it less time-consuming to print banknotes - an especially important feature when the value of money is decreasing every second.

Below are the one hundred thousand Mark note and the two hundred thousand Mark note, both of which are very similar to the fifty thousand Mark note above:

Again, a very plain and simple design for this note. The same lack of imagination and artistic flair can be seen on the 200,000 Mark note as well:

Unfortunately, the 200,000 Mark note would not be the highest denomination currency that the Reichsbank would produce. Far from it, in fact. Because of the rapidly increasing rate of inflation, the need for bills with higher denominations became apparent. Eventually, notes started reaching in the millions of Marks, such as the ten million Mark note below:

As relatively uninteresting as the fifty thousand, one hundred thousand, and two hundred thousand Mark notes had been, they at least made some aesthetic effort, such as colorful watermarks in the background. The background of the ten million Mark note, however, is as bland as could be. It simply reads, “10 Millonen”, which is the German translation of “ten million”. While the font does have some flourishes, the fact that it is in the background makes it nearly unnoticable. The only thing left on the note that is even remotely stimulating are the Reichbank seals, which are found on the lower center left and center right of the note.

But even a ten million Mark note, as inconceivably large as that number is, would not be the end. As the millions were passed, soon billion-Mark notes had to be printed.

Below is a five billion Mark note:

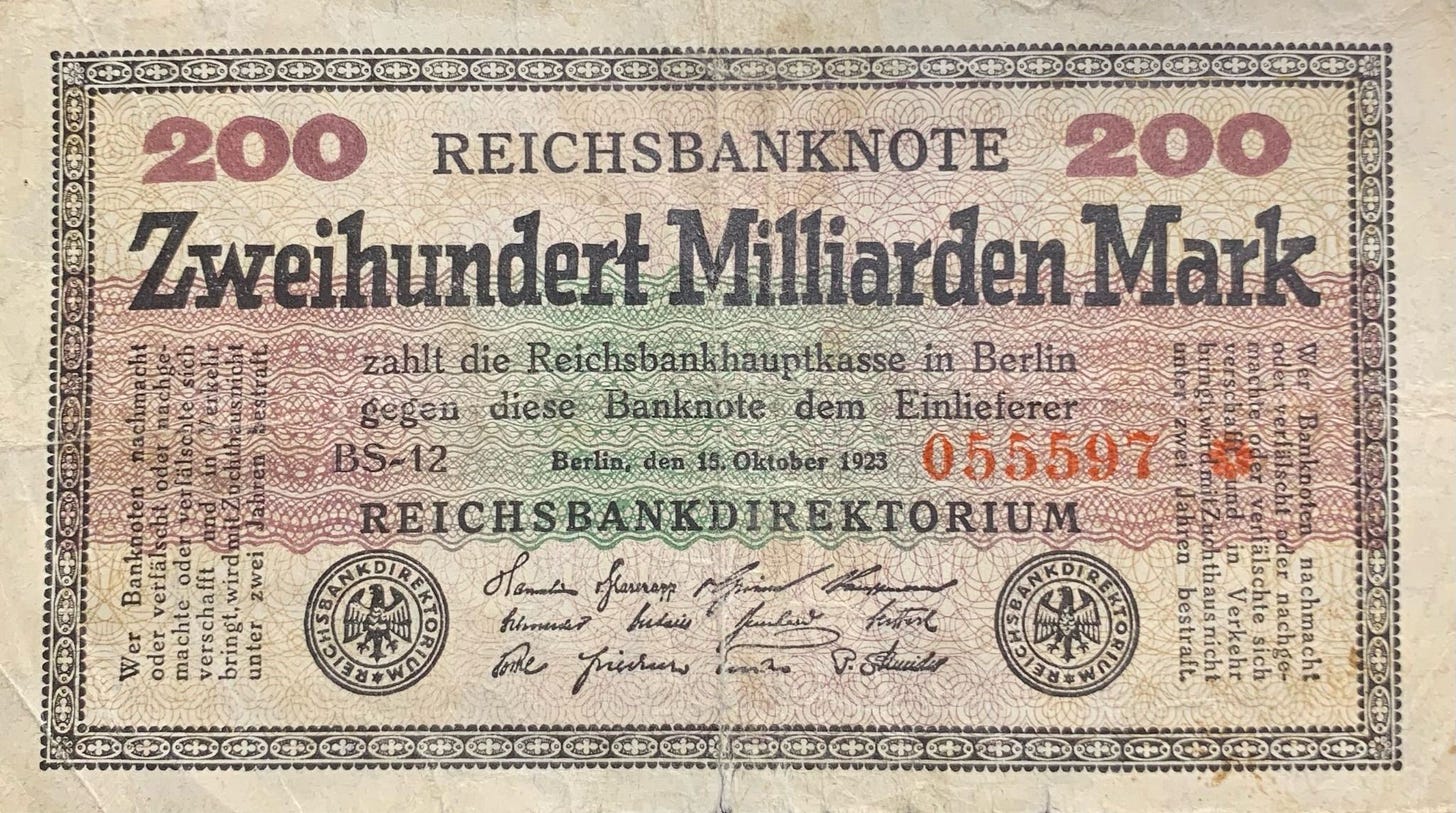

As with all of the other hyperinflationary notes, it has few, if any, notable features. It wasn’t meant to be appreciated or looked at, but simply printed as quickly as possible, distributed as quickly as possible, so it could be spent as quickly as possible, and then discarded just as quickly as it had come into existence. But despite the chaos and destruction that the hyperinflation brought on, the money printing still continued. Below is a two hundred billion Mark note - a number so large as to be nearly unimaginable:

Just for scale, this note’s face value is 40x larger than the five billion Mark note, twenty-thousand times larger than the ten million Mark note, and one million times larger than two hundred thousand Mark note. Yet even still, it was practically worthless. Not even worth the paper that it was printed on. Just like the others, it was not printed for its looks, but just as an ephemeral tool used to survive today and be discarded tomorrow.

As difficult as it may be to believe, there were even larger Mark denominations printed. Before the hyperinflation finally came to a halt at the end of 1923, one trillion Mark notes were in circulation. Unfortunately, I don’t have any of those in my collection. The reason being that when the German government introduced the new stable currency, the Rentenmark, for people to trade their Marks for, the one trillion Mark notes in circulation were still worth something, even if it wasn’t a lot. As a result, many of those were traded in and eventually destroyed. To be sure, you can still find them around, but they cost just a little bit more than what I am willing to pay for worthless pieces of paper (historical value notwithstanding).

I am continually fascinated by the story that these notes tell. It's an old cliché to ask what stories the walls might tell if they could talk, but I can’t help but wonder what kind of stories these notes might tell if they too could talk. Would they tell stories of the frantic economic conditions caused by hyperinflation? Or perhaps about the sorrow and misery that such changes inevitably bring?

Well, unfortunately for us, money can’t talk. But people do! If you are interested in learning more about the German Hyperinflation, I recently did an in-depth podcast on the subject for my show, Marginal Investigations. If you are a fan of history, economics, or just want to learn more about this fascinating time in the past, you can check it out on YouTube, Spotify, or Apple Podcasts. Hyperinflation is a subject that has always fascinated me (hence my collection), and if you are anything like me, I’m sure it will fascinate you too. History that we do not learn, we are doomed to repeat, and hyperinflation is a part of history that no one wants to see repeated.

About the Author

J.W. Rich is an independent writer whose upcoming book is titled Praxeological Ethics. He is also the host of the Marginal Investigations Podcast. Rich’s writings can found here.