Dr. Thomas Szasz: Responsibility, Freedom, and Psychiatry

Another one of the 20th Century's great thinkers that students of Economics should know.

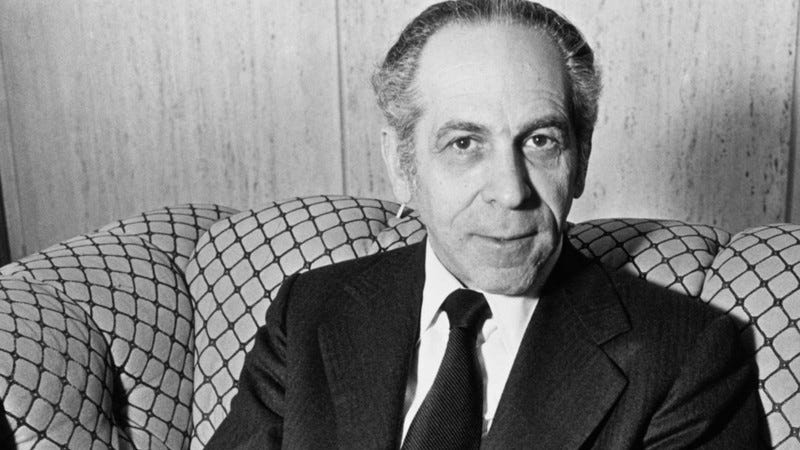

In the world of psychology, there have been influential figures whose work has both illuminated and challenged the field. One such figure is the renowned psychologist Dr. Thomas S Szasz. Born in 1920 in Hungary and later emigrating to the United States, Szasz spent nearly 60 years writing, teaching, and debating as a professor at the State University of New York in Syracuse. His influence cannot be overstated; Szasz wrote on topics from metaphysics, to ethics to politics, and just about everything in between. This article seeks to briefly present some of Szasz’s more profound and popular ideas regarding mental illness, responsibility, and freedom.

The “Myth” of Mental Illness

In his 1961 book entitled The Myth of Mental Illness, Szasz laid out the arguments which thrust him into the academic spotlight for some time. There are chiefly three arguments Szasz made which garnered attention from academia. Szasz defended each of these principles as they were originally presented until his death in 2012.

The Category Error

Szasz draws from British philosopher Gilbert Ryle and his employment of what he calls a category error. Szasz makes the argument that mental illness involves mistakenly labeling socially unacceptable behavior as a medical abnormality. Szasz writes “The norm from which deviation is measured whenever one speaks of a mental illness is a psychosocial and ethical one. Yet, the remedy is sought in terms of medical measures which—it is hoped and assumed—are free from wide differences of ethical value. The definition of the disorder and the terms in which its remedy are sought are therefore at serious odds with one another. The practical significance of this covert conflict between the alleged nature of the defect and the remedy can hardly be exaggerated.”

Brain Disease/Mental Illness

Szasz further introduced the distinction of brain diseases and mental illness. At the time, there had been a huge rise in biological determinism and scientism; the idea that all human phenomena can be explained by physical causes. Szasz explicitly challenged this, and charged that if mental illnesses are said to have biophysical causes, they could not be classified as mental illnesses, and instead must be classified as brain diseases; the implication of this is that psychiatrists are unnecessary and neurological research must be done. Understanding that the “mental illnesses as brain diseases” position was untenable, Szasz presents the idea the mental illness label, unlike the medical sciences, are completely unscientific and value-laden.

He says “We speak of mental symptoms, on the other hand, when we refer to a patient's communications about himself, others, and the world about him. He might state that he is Napoleon or that he is being persecuted by the Communists. These would be considered mental symptoms only if the observer believed that the patient was not Napoleon or that he was not being persecuted by the Communists. This makes it apparent that the statement that "X is a mental symptom" involves rendering a judgment. The judgment entails, moreover, a covert comparison or matching of the patient's ideas, concepts, or beliefs with those of the observer and the society in which they live.”

Problems In Living

Those convinced by Szasz’s arguments began asking the same question as the ones who were not: If mental illness isn’t an illness, then what is it? Clearly there is something going on with this individuals we have labeled as diseased. Szasz answers that they are experiencing problems of living, something which afflicts every human today and historically. By problems of living Szasz “...refer[s] to that truly explosive chain reaction which began with man's fall from divine grace by partaking of the fruit of the tree of knowledge. Man's awareness of himself and of the world about him seems to be a steadily expanding one, bringing in its wake an ever larger burden of understanding (an expression borrowed from Susanne Langer, 1953). This burden, then, is to be expected and must not be misinterpreted. Our only rational means for lightening it is more understanding, and appropriate action based on such understanding.

Personal Responsibility and Freedom

The implications of these three arguments, along with the many others Szasz made over his career, are profound and far reaching. Szasz was a self-described classical liberal and libertarian, and adhered strongly to the political principles of John Locke and the economic principles of Friedrich Hayek. His classical liberal beliefs evolved from his philosophical perspectives on mental health, not despite them. More precisely, though, Szasz believed that individuals were totally responsible for their actions, and ought to bear the consequences of their actions, no matter the circumstances.

One of the areas in which this was applied was in the market of drugs. Szasz maintained that individuals ought to be able to use and exchange any and all drugs. Since these drugs did not constitute harmful, violent offenses, and since no person could suffer from a “mental illness” known as “drug abuse” or “substance abuse”, there was no reason why people couldn’t take drugs. Szasz was strongly against all prescription and patent laws regarding drugs. He derived these positions from the principle of caveat emptor (in latin “let the buyer beware”). That is, in all instances of exchange, it is primarily the buyer's responsibility to inform himself about the product, and if he fails to do that, he should have nobody to blame but himself.

Another political position Szasz held regarding mentally ill patients and their relationship with the law was far more controversial. According to Szasz, psychiatry was not just a medical science, but also a legal institution, as it “exculpated the guilty, and locked up the innocent.” The act of exculpating the guilty was, in Szasz’s opinion, the insanity defense or insanity plea. Since insanity was not a medical abnormality, but rather a collection of behaviors deemed by society to be unacceptable or uncomfortable, having murderers, rapists, and terrorists be hospitalized rather than imprisoned was a huge issue for Szasz on two fronts.

First, the medical profession should not be involved in the process of prosecuting or defending criminals, as that is not the job of a physician or therapist. Second, that the medicalization of criminal behavior, in this case the insanity defense, results in the abolition of evil: “Why would criminals need psychiatric evaluation, if the presumption was they would not done what they have done unless there is something wrong with them. There is no evil.” What Szasz is getting at here is another employment of the category mistake; applying the “medical disease” of insanity to criminal behavior pushes the discussion out of the appropriate moral kind into the inappropriate medical kind. In other words, the question no longer becomes if one is good or evil, but if one is normal or insane.

The other side of the coin, locking up the innocent, is known as civil commitment, whereby depressed, bipolar, schizophrenic, or other presumed to be mentally ill individuals are hospitalized against their will “for their own good.” Not only did Szasz oppose this on traditional libertarian grounds, that these individuals had committed no crime, but also on the grounds that the justification for civil commitment was based on paternalism. “Every country in the world has, almost verbatim, a law which states an individual may be locked up if he is “a danger to himself or society.” Szasz saw this paternalistic law as completely unjust, explaining that all adults are held to be responsible for their actions unless there is a demonstrable, physical ailment from which they suffer.

Conclusion

The work of Dr. Szasz cannot be overstated. The implications of his original arguments on politics, economics, and even metaphysics and epistemology is broad and profound. Every student should familiarize themselves with the work of Dr. Szasz, if not for the sake of truly grasping what he has to say, then at least to be challenged by something they probably disagree with.

Recommended Reading

1. "The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct" (1961)

2. "The Manufacture of Madness: A Comparative Study of the Inquisition and the Mental Health Movement" (1970)

3. “A Lexicon of Lunacy: Metaphoric Malady, Moral Responsibility, and Psychiatry” (1993)

4. “The Meaning of Mind: Language, Morality, and Neuroscience” (1996)

5. “Insanity: The Idea and Its Consequences” (1997)

These books provide a comprehensive overview of Thomas Szasz's ideas and their lasting impact on the field of psychology and mental health care. Reading his works will undoubtedly spark contemplation and further exploration of the complex issues surrounding mental illness and personal freedom.

Do you want to learn more about Austrian Economics and libertarian philosophy? But can never find the time?

I love listening to podcasts on my daily commute or while doing chores like cooking. I have been able to squeeze in so much learning this way. The convenience of podcasts are amazing.

That’s why I really love Tom Wood’s Liberty Classroom. One of the best places to learn about Economics and Libertarian Philosophy.

Liberty Classroom is like podcasts on steroids. Because each professor has put a ton of focused effort into their courses. So, there is never any fluff like with a lot of podcasts out there. Meaning, none of your time is wasted.

More importantly, you can listen to any course just like a podcast saving you time. Super convenient.

There are also video you can watch as well, if you want. Whatever works best for you.

Dozens of online courses you can watch or listen to at anytime for one affordable price.

Liberty classroom is super affordable and I highly recommend you clicking on the link below and purchasing access now.